Investigation into the origin of a misunderstanding

This text is a translated compilation of several articles gathered on this site under the name “Bellagio Misunderstanding”.

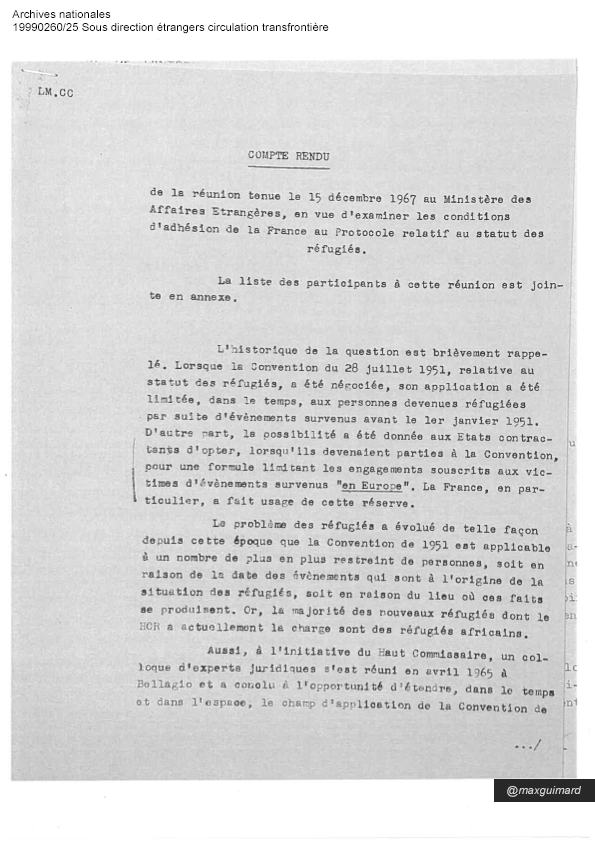

Until the 1970s, the right to asylum, enshrined in the 1951 Geneva Convention, was only applicable to populations who had fled events in Europe prior to that year, as per a clause in its first article.

It was under the impetus of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) that a conference was organized in April 1965 at the Villa Serbelloni in Bellagio, Italy, to address contemporary refugee issues. This led to the drafting of a protocol that removed these geographical and temporal limitations, which was then communicated to the United Nations General Assembly, urging member states to adhere to it.

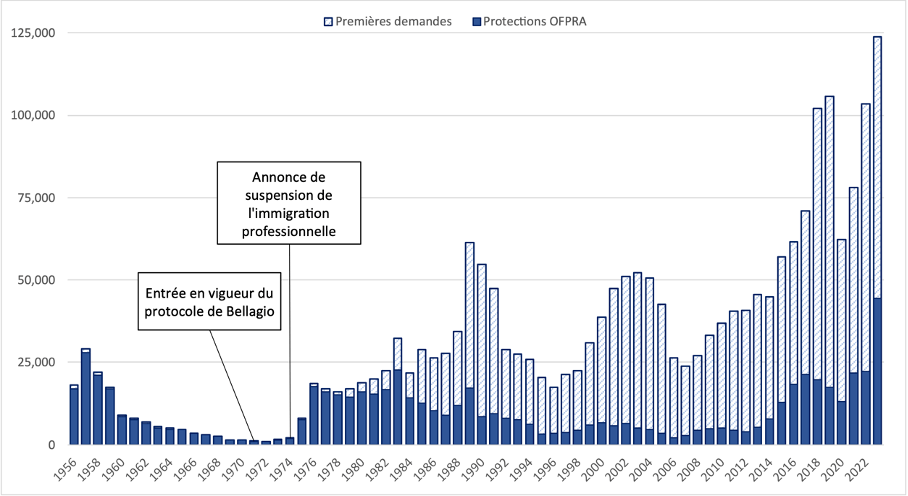

This text had a major impact on all policies related to borders or immigration, as it now allows asylum seekers to stay in the country during the examination of their applications. For example, upon arrival at the external border of Europe, a person lacking the necessary documentation may invoke fears of persecution to be admitted to the territory. Since the entry into force of this amendment, more than 2 million people have applied for asylum in France, and over 500,000 have been granted protection. The text is also central to legal debates concerning the handling of asylum seekers at the southern border of the United States.

Despite the importance of asylum in the domestic policy of participating states, the conditions of their adherence to the so-called « New York Protocol » or « Bellagio Protocol » remain little studied today. In France, when the law of adherence to the protocol was presented to the National Assembly on October 14, 1970, no deputy asked to speak. The Senate also unanimously approved the bill.

Indeed, during the 1960s, asylum applications had gradually decreased, as the pool of individuals eligible for protection dwindled with the fading of Europe’s partition. But by 1976, just three years after the text came into force in France, the number of asylum applications had increased more than tenfold compared to the previous period. They would never again drop below 15,000. In 2022 alone, over 100,000 asylum applications were filed in France.

In the case of France, to what extent were these data anticipated and predicted by the authorities involved in the accession process? In other words, did the actors make a forecasting error regarding the actual impact of the text and the dynamics of future population movements (error thesis)? Or was their choice the result of an informed decision and realistic perceptions of the future consequences of the document (choice thesis)?

The Error Thesis

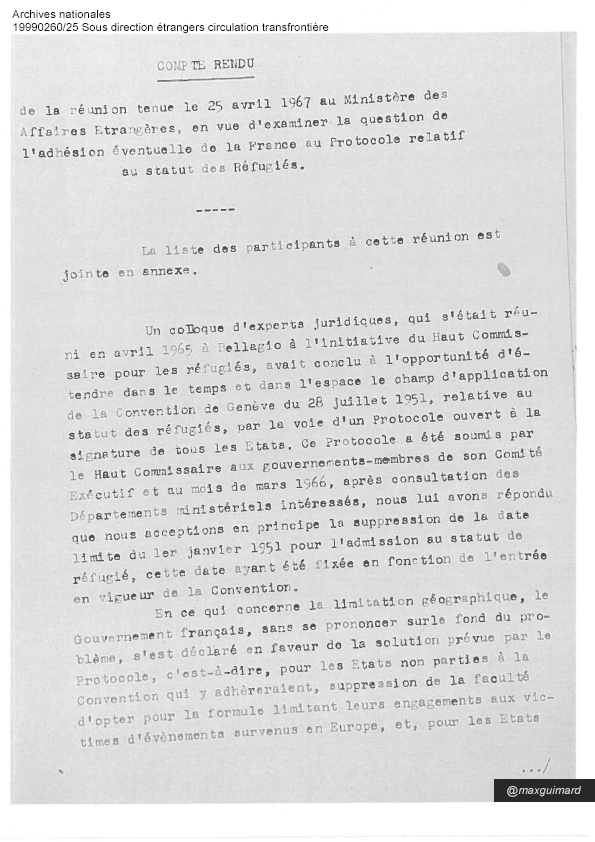

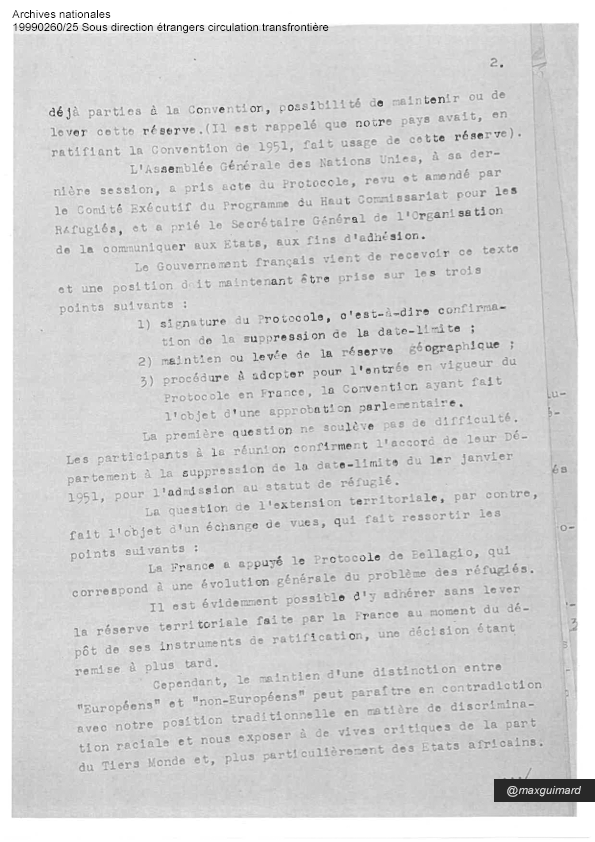

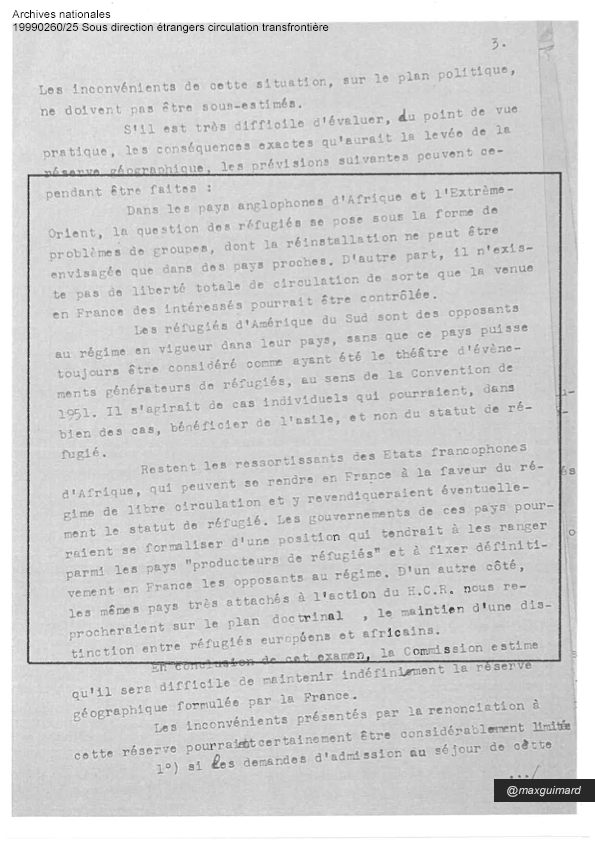

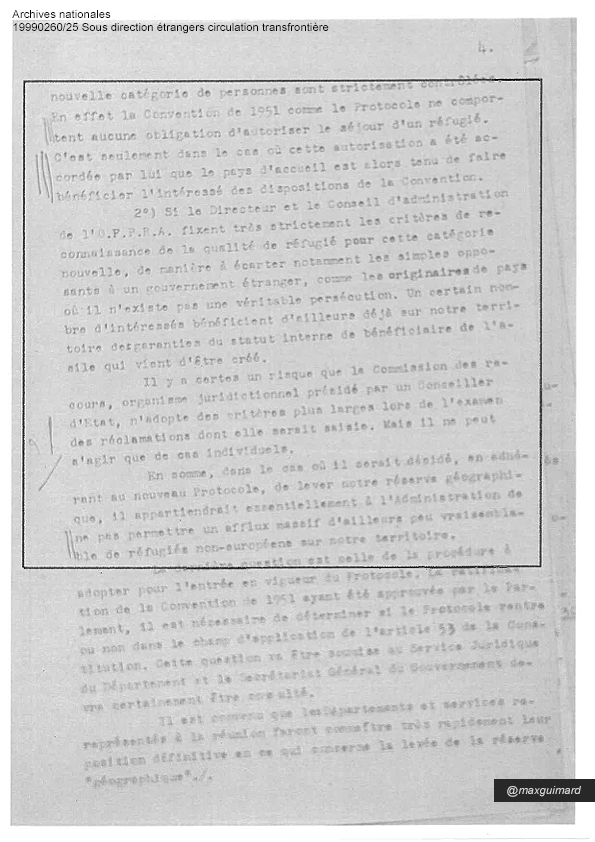

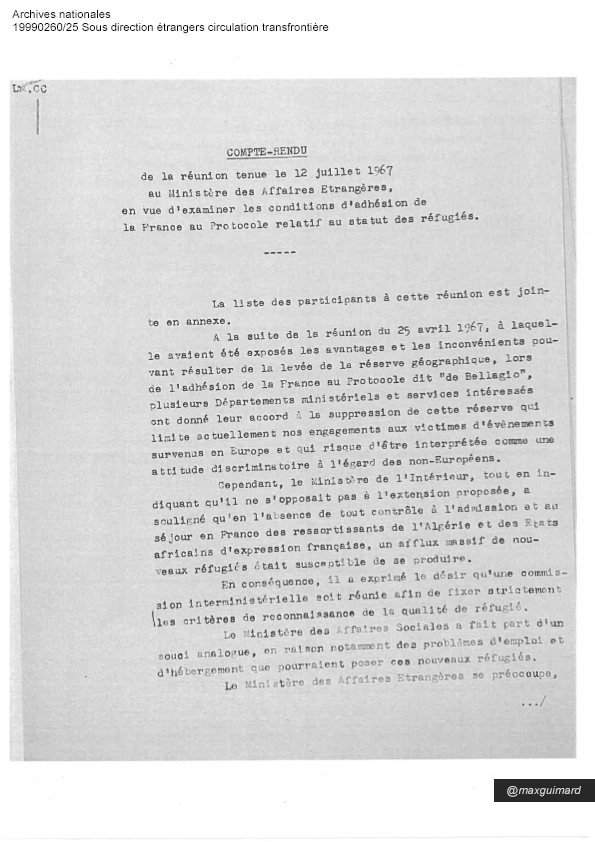

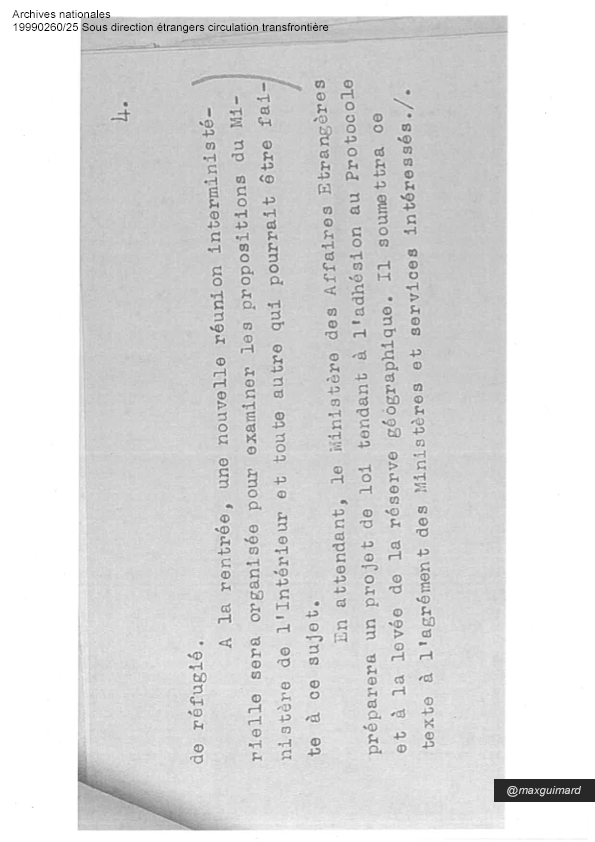

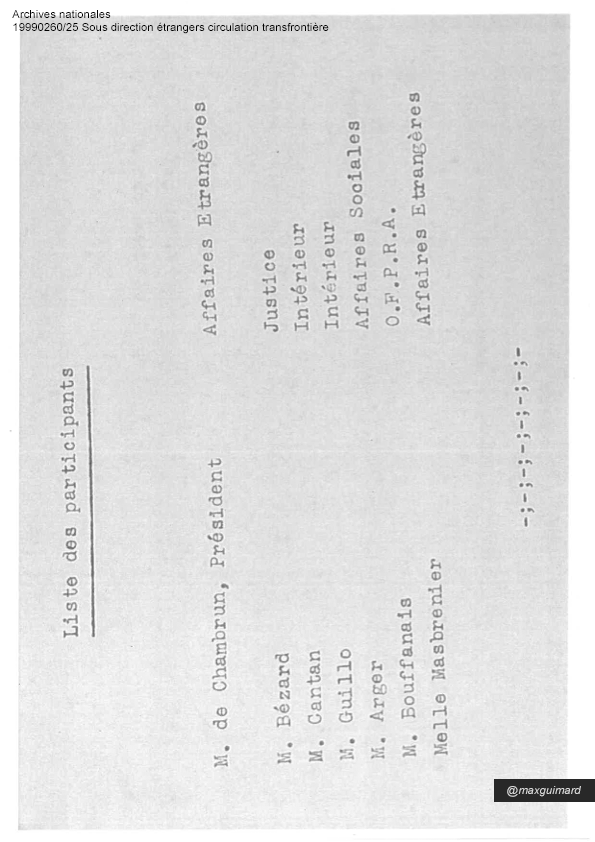

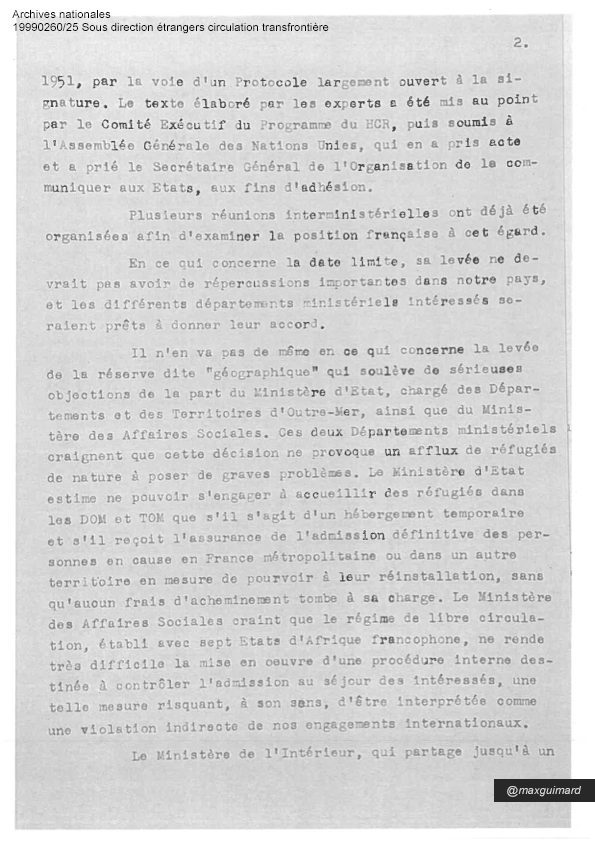

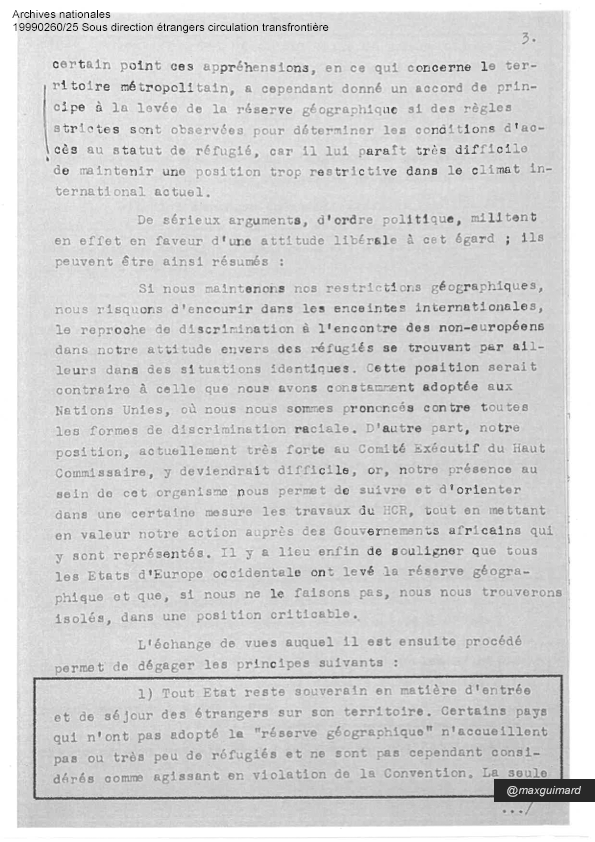

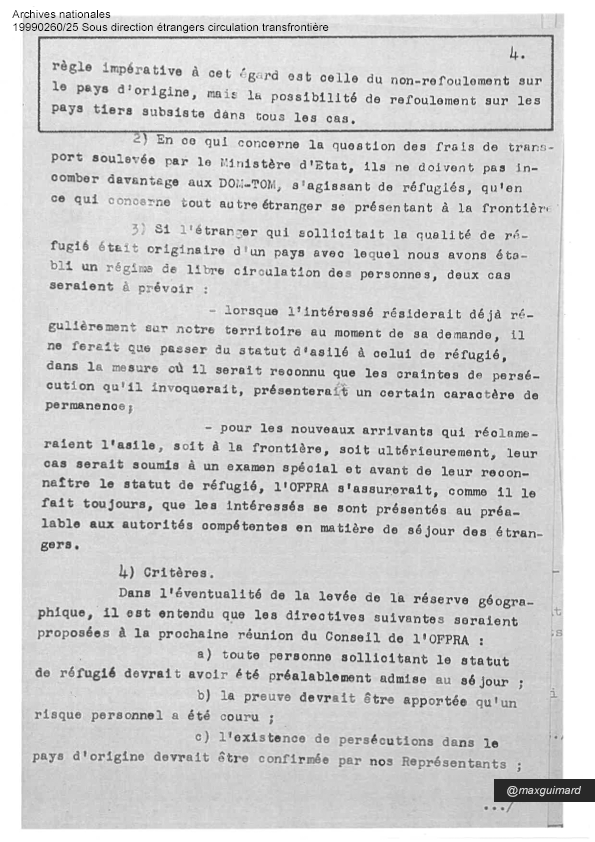

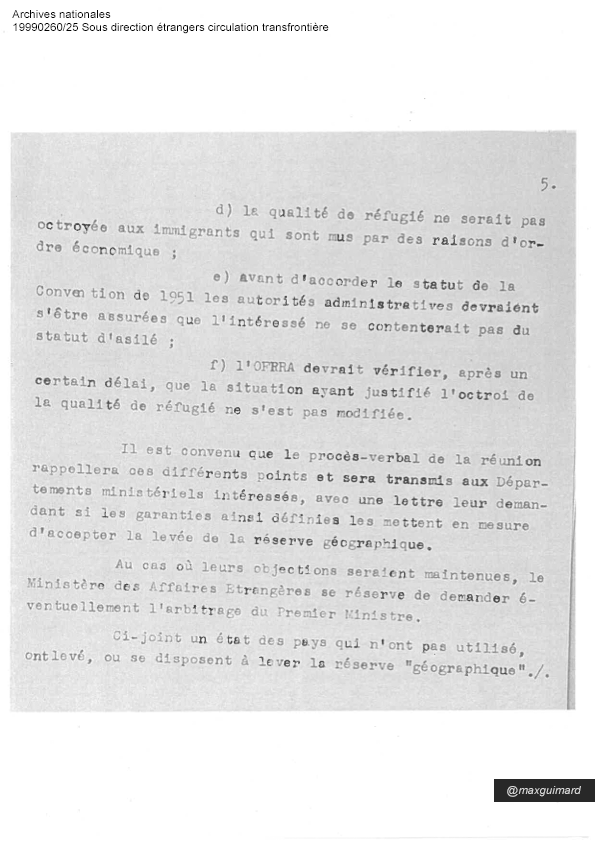

While an international comparative study of the conditions under which the Bellagio Protocol was imposed is still lacking, documents from the archives of the Ministry of the Interior’s Directorate of Regulations (now DLPAJ) provide a fairly clear account of the nature of the debates that took place in France in 1967 among the various administrations concerned with the text. A reading of the conclusions of several interministerial meetings (RIM) later transmitted to the relevant ministers and the repeated analyses in parliamentary commission reports make the error of diagnosis thesis manifestly evident.

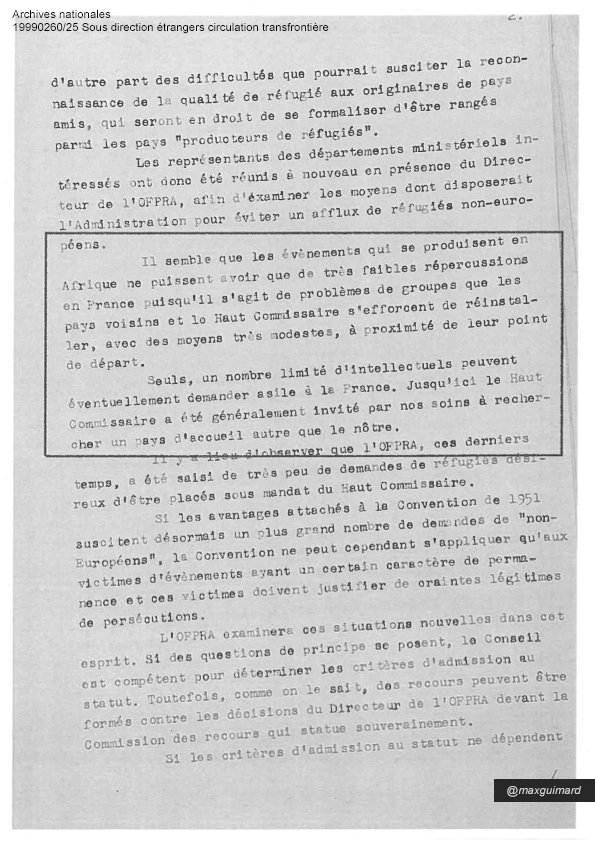

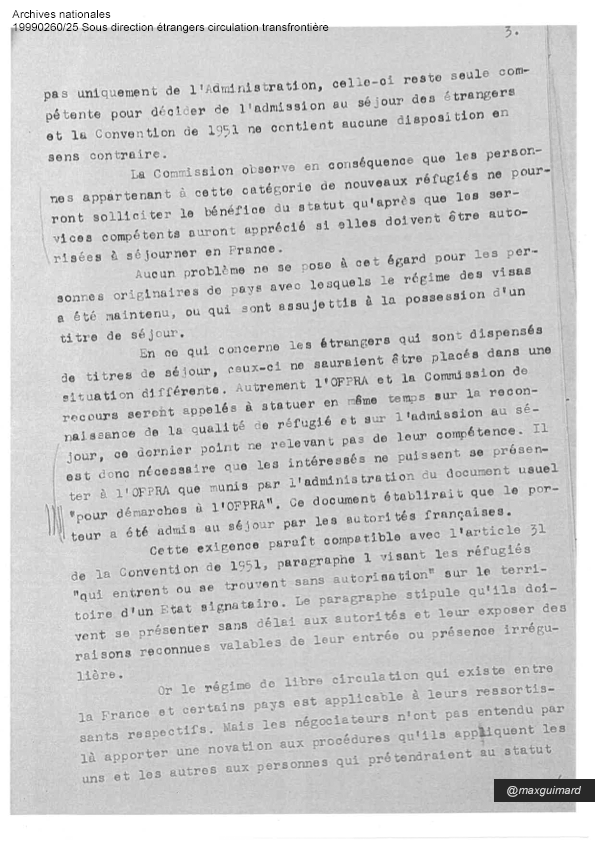

Indeed, according to the archives, the accession to the protocol was not expected to result in any substantial changes in migration flows or residence or border-crossing rules. According to the conclusions of the interministerial meetings, asylum rights should « exclude mere opponents of a foreign government » and the protocol would « not entail any obligation to allow a refugee to stay. » Furthermore, it was believed that « events occurring in Africa could have only very limited repercussions in France, as these are group problems that neighboring countries and the High Commissioner are trying to resolve with very modest means near their point of origin. Only a limited number of intellectuals might possibly seek asylum in France. » Finally, it was reaffirmed that « each state remains sovereign in matters of the entry and stay of foreigners on its territory. »

All these assertions were contradicted by the subsequent evolution of both flows and legal procedures in the following years. It is therefore hardly contestable that the information produced in interministerial meetings and subsequently made public did not enable the public or parliamentarians to make an informed decision on the changes that followed the accession to the protocol. This « Bellagio misunderstanding » sheds new light on the origin of contemporary asylum law, which is often perceived today as unanimous, consensual, and self-evident.

These archives are now freely accessible but have not yet been published. Here is a reproduction of them, made by myself.

From Colloquium to Protocol

The nature of the exchanges between the ministries of foreign affairs, the interior, social affairs, and overseas territories unequivocally betrays an error in diagnosis. However, these documents alone are not sufficient to account for the complexity of the exchanges that took place upstream of the interministerial discussion. These archives say little—indeed, almost nothing—about what the Ministry of Foreign Affairs believed it was accepting and the attitude of the UNHCR, the promoter of the text.

Indeed, while it is evident today that refugee movements to Europe were not limited to « a few intellectuals, » it must be considered that these developments were independent of the initial intentions of the text’s drafters. Conversely, it may be imagined that this evolution was anticipated, or even encouraged, from the project’s inception. The obvious question that arises is whether the erroneous diagnosis we have highlighted was spontaneous or deliberate.

The fact that the Bellagio Protocol was imposed without difficulty and simultaneously in all Western democracies—where these legal conventions are now fully in effect—suggests a hypothesis of information asymmetry created by the drafting body, the UNHCR. However, it is also possible that clear provisions were communicated to the administrations in charge of foreign affairs, which were then reformulated to their advantage in the context of national debates. Finally, it is also conceivable that no one in 1967 foresaw the future developments in asylum law and associated migration movements, even in the short term.

To attempt to answer these questions, it is necessary to consult the archives of each of the actors involved, particularly those in Geneva. However, quite unusually for an international convention, the Bellagio Protocol was not at the center of an international conference gathering the delegations of the future signatory countries to debate the content of the draft. On the contrary, the text was drafted by a small group of nineteen experts who met in the luxurious Villa Serbelloni near Lake Como in April 1965. As a result, it is not possible to review the preparatory work of the Bellagio Protocol as one might with, for example, the Geneva Conferences on the Protection of Civilians in Time of War. No final act of the meeting was published. Furthermore, the draft protocol, subsequently sent by the High Commissioner to the United Nations General Assembly, was adopted there without debate. This is because prior negotiations primarily took place through informal meetings and bilateral exchanges.

Fortunately, a Canadian academic, Robert F. Barsky, gathered an impressive collection of documents related to the development of the Bellagio Protocol from archival sources of the United Nations, the Carnegie and Rockefeller Foundations—which financed the initiative—and private libraries. The researcher’s primary intention was to defend the rights of refugees in the United States, since this country, not a signatory to the 1951 Geneva Convention, only connects to the international asylum regime through the single protocol it adhered to in 1968. The administration of Lyndon B. Johnson was indeed very favorable to this, and, as in France, the efforts undertaken by the State Department with the Senators successfully secured a unanimous vote (98-0) in favor of the text.

These studies reveal that the development of the protocol took place in the context of the Cold War. The experts at the conference wished to extend the asylum regime but were pressed for time, as regional agreements such as the 1969 Convention of the Organization of African Unity and the 1984 Cartagena Declaration—for Latin America—were expanding the definition of a refugee to include those fleeing war or serious public order disturbances. Several regions of the world also felt that the Geneva Convention did not concern them due to its geographical and temporal limitations. Thus, the approach of a universal convention was not universally accepted, and the UNHCR likely feared a fragmentation of asylum law, and consequently of its own mandate. Additionally, the United States seemed willing to sign a new treaty immediately to mark a victory against the Soviet Union, which presented a new window of opportunity.

For these reasons, even though the international asylum regime was intended, from the perspective of its proponents, to be progressively expanded in a more liberal direction, the experts agreed on a minimalist draft that, in a single article, could universalize the 1951 Geneva Convention. In such circumstances, the experts’ efforts focused mainly on convincing the largest number of states to adhere to the text. For example, the idea of a suspension clause for the convention’s obligations in times of crisis was considered, which might have reassured potential signatories, but was ultimately rejected to avoid weakening the guarantees.

The promoters of the text, particularly Ivor Jackson and Paul Weis, legal experts at the High Commissioner’s office, were also concerned with the conditions under which the Protocol would be adopted. They recommended that it not be subjected to discussion by the General Assembly. Another solution mentioned in the archives was to present the draft to the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) to avoid a discussion in a general session. The third possibility, and the worst, would be to convene a conference of the States Parties to the Geneva Convention. During the summer, it was suggested that the protocol be included in the UNHCR’s annual report « to avoid raising too much discussion. » On October 13, 1965, the High Commissioner sent a letter to all 58 States Parties to the 1951 Convention to gather their opinions on the draft protocol.

He received more than a dozen responses within a few months, including one from the Netherlands, which proposed, instead of removing the 1951 limit, adopting a new deadline. The ambiguous responses from many states continued to worry Paul Weis, the UNHCR’s legal director, who feared that they might precipitate the organization of a conference of plenipotentiaries. For this reason, the option of a « calculated risk » by quickly presenting the protocol to the General Assembly before opening it for signature was chosen, as suggested by Ivor Jackson. It was hoped that no delegate from the Standing Committee on Human Rights would raise any concerns. This approach proved successful, as by October 1967, just a few months after the text was presented by the then High Commissioner, Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan, several countries had already deposited their instruments of ratification or accession.

The remarkable work of Robert F. Barsky helps us understand that the main concern of the involved actors was to create a truly universal legal regime for the protection of political refugees, without it being possible to attribute to them the intention of making it a tool for advocating freedom of movement. However, the sources used, as reported by this academic—who himself is a promoter of asylum rights—abundantly emphasize that all the experts and diplomats involved were fully aware of the sensitive nature of their work and skillfully maneuvered to make it as discreet as possible.

Nevertheless, these Bellagio papers bring us back to the same impasse encountered in our French study: knowing what international organizations had in mind does not allow us to conclude what national diplomats understood from it, let alone what the national representation ultimately agreed to.

The Diplomatic Filter

Consulting diplomatic archives has now become inevitable to gain more information on the attitude of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Quai d’Orsay). Three hypotheses can be proposed:

- The Ministry of Foreign Affairs might have had relevant information about the future of asylum law or guessed the intentions of the international organization but chose to defend a misleading interpretation to other government agencies to prioritize its bureaucratic objectives (the diplomatic filter thesis), namely, France’s respectability or international image.

- The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) might have promoted a minimalist and reassuring interpretation of the protocol’s obligations to Western states, including by means of deception, in order to hasten their adherence (the autonomous organization thesis).

- Finally, each actor might have worked in good faith and with complete transparency with their counterparts, but none had realistic forecasts concerning the future of asylum law and related migration movements, even in the short term (the ingenuous thesis).

Research conducted at the Diplomatic Archives in La Courneuve (93) only partially answers these questions and, at this stage, does not decisively rule out any of these hypotheses. The UN Directorate at the Quai d’Orsay, which serves as the contact point in Paris for the French representation at the High Commissioner’s office in Geneva, clearly stated internally its primary objective: not extending asylum rights « could risk exposing us, in the current context, to potentially harsh criticism from the Third World, particularly African states. » The director, Guy de Lacharrière, wished to compare the disadvantages « to which some ministries seem highly sensitive » with those that, on the political level, would result from maintaining the current discriminatory status.

Unsurprisingly, international costs appeared predominant in the assessments made by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, while internal costs were of much greater interest to ministries dealing with domestic matters. In this context, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs may have had an interest in pushing other government agencies to act.

However, in the course of my research in the most relevant collections, I did not find any documents indicating that analyses within the French diplomatic services were not shared in interministerial meetings with other ministries.

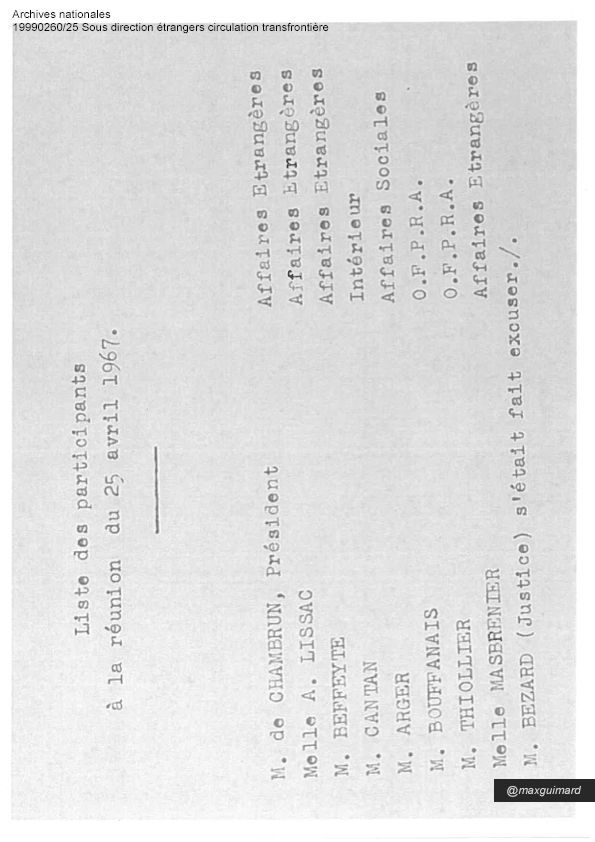

The main player in discussions at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Paris was the Director of Consular Affairs (now DFAE), first François Leduc, then Gilbert de Chambrun. But the French delegation to the UNHCR Executive Committee meetings often included representatives from other ministries, including the Ministry of Social Affairs and the Ministry of the Interior, who were primarily concerned with migration issues. Maurice Cantan, Deputy Director of Regulation at the Ministry of the Interior, not known for leniency on migration issues, and François Villey, a senior civil servant, were among the high-level representatives. As early as 1966, Villey reported to the Minister of Social Affairs that it « is not appropriate to make an artificial distinction between old and new refugees, » and that the « UNHCR can only intervene temporarily in resettlement programs ». Thus, the Quai d’Orsay did not hold a monopoly on information regarding the Bellagio Protocol when it discussed its ratification with other government agencies in 1967.

On the other hand, it does not seem that the Quai d’Orsay initiated consultations before committing the French government to the UNHCR delegate in France. This point is significant because international custom and treaty law oblige signatory states to refrain in good faith from acts contrary to the treaty’s purpose before its entry into force. In this case, the Quai d’Orsay appears to have skillfully used these circumstances, albeit moderately, to pressure reluctant or skeptical administrations. For example, the Minister of Overseas France, Henri Rey, wrote:

« The financial problem remains unresolved. The costs of housing and transporting refugees in the overseas departments and territories cannot in any way be borne by my department’s budget, nor by those of the overseas territories […] The agreement I am inclined to give, to take into account the international political reasons you invoke, will not solve all the problems I previously raised, which may one day arise on the domestic front […] Since it does not seem possible to delay the ratification of this Protocol any longer by citing internal difficulties that would be hard to recognize and accept internationally, I can only bow to your decision. »

Henri Rey, Minister of Overseas France

Finally, while there appears to have been no omission in informing the government, it is notable that several arguments frequently reappear in the conclusions of interministerial meetings throughout 1967, which extended over several months, as well as in parliamentary committee reports, without ever having been previously presented within the UN system. For instance, the already mentioned assertion that « every State remains sovereign regarding the entry and stay of foreigners on its territory » constitutes an ad hoc argument, not a guarantee provided by the UNHCR. The idea that refugee status granted by OFPRA (French Office for the Protection of Refugees and Stateless Persons) would remain contingent on residence approval by the Ministry of the Interior, which was advanced during arbitration meetings on September 21 and December 15, 1967, is also an internal legal invention, particularly surprising given the very purpose of the convention. The Secretary-General for the Police, Jacques Aubert, was not deceived, as his agreement to lift the geographical reservation was only secured on the condition that « the criteria for recognizing refugee status are strictly defined ».

From this cursory research, it does not appear that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs had any information it deliberately withheld from other government agencies. However, it does seem that the Ministry pursued its own objectives by resorting to the fairly common strategy of presenting a fait accompli, while advancing a rather baroque legal argument, which would be contradicted a few years later.

Nonetheless, was this attitude the decisive factor in France’s decision? In other words, would France have adhered to the protocol without these elements? I tend to believe so, but it is impossible to know for certain without conducting a comparative study of each country that adhered and investigating the reasons for the other states’ adhesion to the Bellagio Protocol, as it seems unlikely that all Western chancelleries would have adopted the same approach by coincidence.

Ancient and new Refugees

A more in-depth exploration of the political context of the time and the role of the High Commissioner for Refugees could further clarify the mystery.

Since the Geneva Convention only applied to European refugees resulting from events prior to 1951, the number of eligible populations inevitably declined over the following years. Additionally, the 1960s marked a turning point for the High Commissioner for Refugees, which was clearly perceived by the concerned parties.

Indeed, the refugee issue was not exhausted by European peace, and numerous population displacements were observed in Africa due to decolonization or internal conflicts in newly independent countries. In this context, the High Commissioner developed a strategy of increasingly intervening in developing countries under its bons offices*.

The issue of the « new refugees » thus taken in by the United Nations gradually began to replace that of the « old refugees » designated by the Geneva Convention. In 1962, High Commissioner Félix Schnyder appointed Sadruddin Aga Khan, the son of a Frenchwoman and a Persian diplomat and religious dignitary, as his deputy. The young prince enjoyed widespread sympathy in the Third World and the support of the Ismailis.

The Director of Administrative and Social Affairs (Convention Service) at the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, François Leduc, noted that this appointment « confirms the shift in the policy of the High Commissioner for Refugees, » which was then led by a Swiss national. He continued:

« Mr. Schnyder believes that his main mission will now be to lend his good offices to provide international assistance to all victims of military and political events outside Europe. He is therefore reshaping the composition of his office, which he finds insufficiently representative of the different parts of the world where he intends to operate his activities. »

This evolution sparked some concerns within the Quai d’Orsay and other donor countries, including the United States:

« Mr. Schnyder had succeeded in avoiding, on the one hand, the politicization of African refugee issues, and on the other, the excessive increase in expenditures on this continent, where 500,000 refugees were counted. It would be regrettable if his successor, who will be subjected to numerous pressures, did not exercise the same caution. It is also feared that the issue of European refugees will be increasingly neglected in favor of African and Asian issues. »

At the time, however, the concerns did not involve the possible future transfer of these new refugees to Europe but were more financial and political in nature.

From a budgetary standpoint, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs wished to retain control over French contributions. Since the High Commissioner for Refugees is funded only by voluntary contributions from states, negotiations for additional funding mobilized significant energy each year from the Foreign Minister’s office, in coordination with the Ministry of Finance. The emergence of the « new refugee » issue thus worried the Quai d’Orsay, whose resources were not infinite. For example, it was proposed that France withdraw from the Intergovernmental Committee for European Migration (the precursor to today’s International Organization for Migration), whose « excessive staff, constantly increasing operating costs, and budgetary disorder are almost unanimously criticized. » The associated funds were reallocated to the High Commissioner for Refugees, but about ten years later, France would reintegrate this organization, rehabilitated in the eyes of the administration.

The political risk lay in a concern that has entirely disappeared today, namely, offending persecuting countries. The Director of Consular Affairs noted that « the tendency of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees is to extend this status to anyone who has had to flee any country for political reasons. » Such extensions, however, « could put us in a delicate situation with certain countries, offended to see it suddenly recognized that there are persecutions in their territory. » The example of Portugal, still led by Antonio Salazar, is mentioned.

Whatever these apprehensions, Prince Aga Khan gradually won the approval of the chancelleries. UN Secretary-General U Thant hesitated for a time to propose him as a replacement for Félix Schnyder as High Commissioner, believing him to be Pakistani, but eventually decided in his favor. Aga Khan was elected in 1965 to replace Mr. Schnyder. He met General De Gaulle on March 14, 1966, and maintained very cordial exchanges with Georges Pompidou in 1970.

The Bellagio Protocol, by removing the limits on the scope of the Geneva Convention, was intended to realize the ambitions of the High Commissioner for Refugees and address the uncertainties faced by non-European host countries. This was the motive advanced by the High Commissioner, confirmed by the practice at the time, which was not aimed at the relocation (or resettlement) of refugees outside their region of origin to developed countries.

The archives, from the perspective of French diplomacy, do not dispute this representation. It is true that the High Commissioner occasionally asked France to take in a dozen Haitian refugees hosted in the Dominican Republic, but this practice was ultimately rare, as evidenced by the data published by the UN on resettlements carried out since 1959.

Indeed, until the late 1970s, the High Commissioner did not consider resolving refugee issues other than by hosting them near the regions they had to flee. Resettlement in another continent was carried out on a voluntary basis by host countries, and the Bellagio Protocol did not bring about any change in this legal situation. The practice developed from the late 1970s with the crisis of the Boat People, provoked first by the fall of Saigon and then by the war between Vietnam and Cambodia.

However, from the 1970s onward, the United Nations began to intervene in the administrative and legislative debate to promote a more liberal approach to processing refugee claims. On the occasion of a planned meeting in 1972 between High Commissioner Aga Khan and Foreign Minister Maurice Schumann, the cabinet prepared talking points directly revisiting the conclusions of the arbitration taken five years earlier:

« Another problem that also causes complaints or criticism = the excessive dependence of OFPRA on the Ministry of the Interior; administrative practices that unduly reduce the role of OFPRA, whose intervention is now subject to the prerequisite of residency admission. » […] « The distinction between non-refoulement and residency admission is legally defensible. Politically, it does not hold up to scrutiny, considering the consequences and possible abuses, France’s long-standing tradition in this area, and the pioneering role it has played in this regard.«

A modification was thus proposed to circumvent the prior procedure of obtaining a residence permit from the Ministry of the Interior. The behind-the-scenes developments in the subsequent periods are still inscrutable, but procedural changes would gradually dismantle the safeguards that the Ministries of the Interior and Social Affairs believed they had secured in 1967. In 1982, a procedure was instituted to allow a foreigner to enter the territory without authorization if they claimed persecution. In 1992, a right of review by the United Nations High Commissioner in the border procedure was enshrined in law. The law also specified that « admission cannot be refused solely on the grounds that the foreigner lacks the [required] documents and visas. »

It is therefore likely that it was during the 1970s that attitudes toward the asylum system established a decade earlier were significantly transformed, although it cannot be said that the High Commissioner had these changes in mind at the time.

To go further, in-depth work in the La Courneuve archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs should still be carried out. A comparative approach to interactions between chancelleries and the institution of the High Commissioner for Refugees, based in Geneva, would also provide answers to the hypothesis of a provoked error.

* In international relations, the intervention of a neutral third party in a conflict between states to help resolve it.

Archives

MAE 517INVA/790, Note du 7 juin 1968 sur l’extension de la Convention de Genève de 1951

MAE 11POI/1/364, Note à l’attention du ministre des affaires sociales du 31 mai 1966

MAE 11POI/1/364, Lettre au Haut-Commissaire, 21 mars 1966

MAE 517INVA/790, Lettre 302/CABM du 4 août 1969 au ministre des Affaires étrangères

AN 19990260/25, Courrier du ministre de l’Intérieur pour la Police au ministre des affaires étrangères du 15 juin 1967

MAE 12QO/219, Note pour le cabinet du ministre du 6 février 1962 – 301 00677

MAE 12QO/219, Note pour le cabinet du ministre du 8 octobre 1965

MAE 12QO/219, Note pour le ministre du 31 octobre 1962

MAE 12QO/219, Note pour le ministre du 2 juin 1966

MAE 498INVA/1691, Note pour Bertrand Dufourcq du 13 mars 1979

MAE 12QO/219, Note pour le cabinet du ministre du 28 octobre 1966

MAE 11POI/1/364, Télégramme du représentant permanent à Genève du 6 octobre 1965

Bibliography

Maxime GUIMARD, Petit traité sur l’immigration irrégulière, Editions du Cerf, 11 janvier 2024, 384 pages

Robert F., BARKSY (2020). From the 1965 Bellagio Colloquium to the Adoption of the 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees. International Journal of Refugee Law. 32. 340-363. 10.1093/ijrl/eeaa013.